By Jorge Costa Oliveira

Partner and CEO of JCO Consultancy

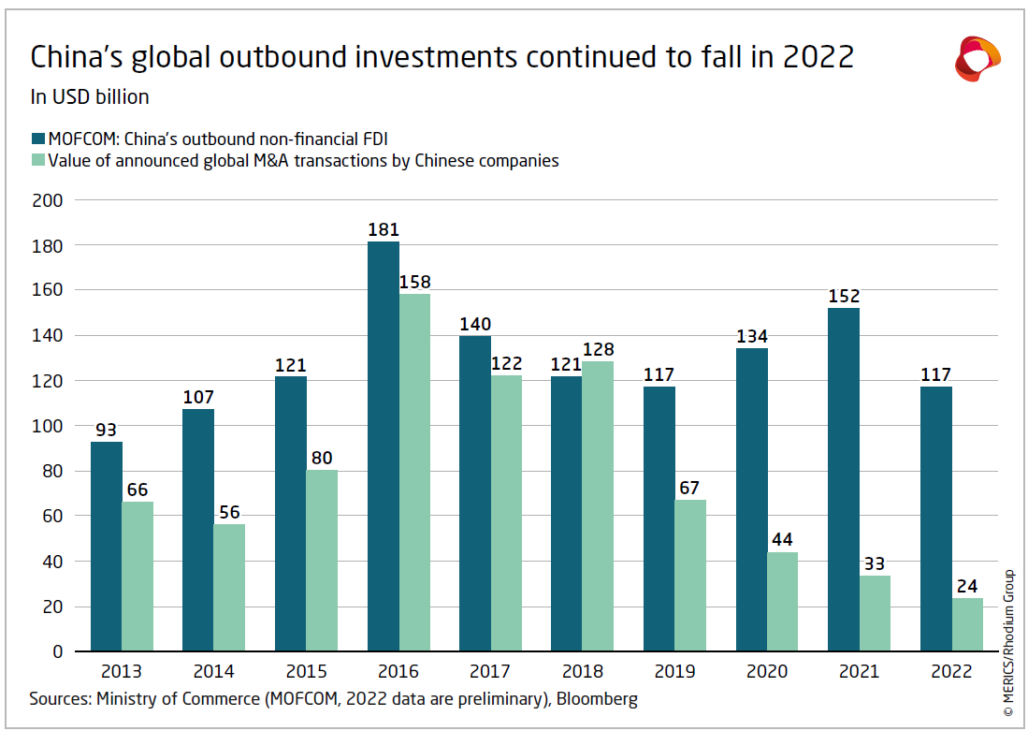

According to a recent report by the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) and the Rhodium Group, global Chinese outbound foreign direct investment (OFDI) fell by 23% in 2022 from the previous year, to USD 117 billion, an 8-year low. China’s outbound mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activity also dropped, falling 21% year-on-year (y-o-y) to a total of USD 24 billion.

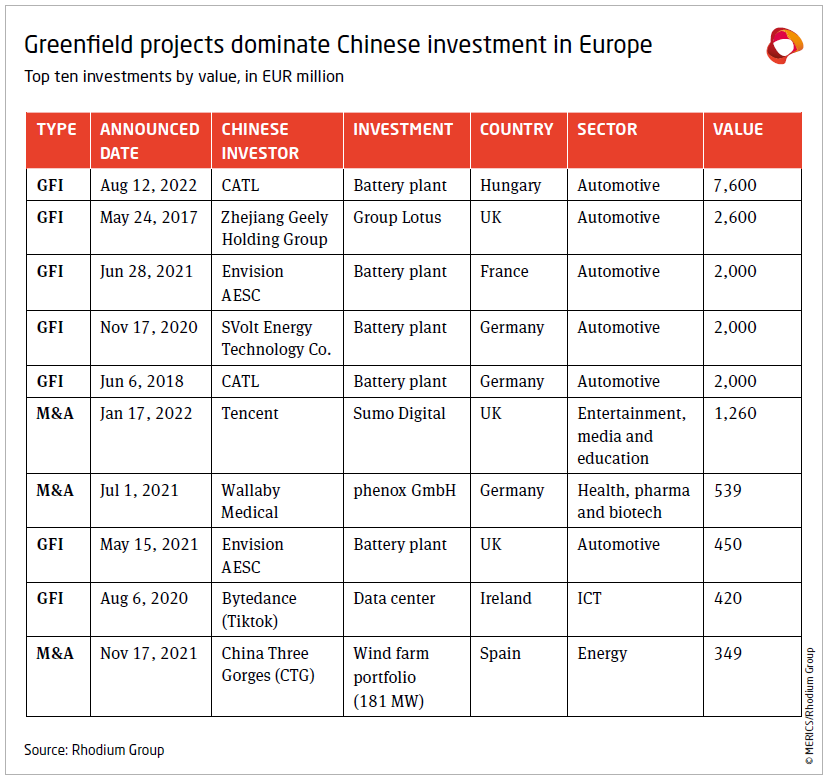

FDI in Europe originated in China has declined to $8.7 billion, a 22% fall y-o-y. The drop takes Chinese investment in Europe back to its 2013 level. Less Chinese M&A transactions seem to be the main reason. Only Tencent’s purchase of British video game developer Sumo Digital was of significant value (>1 billion euros).

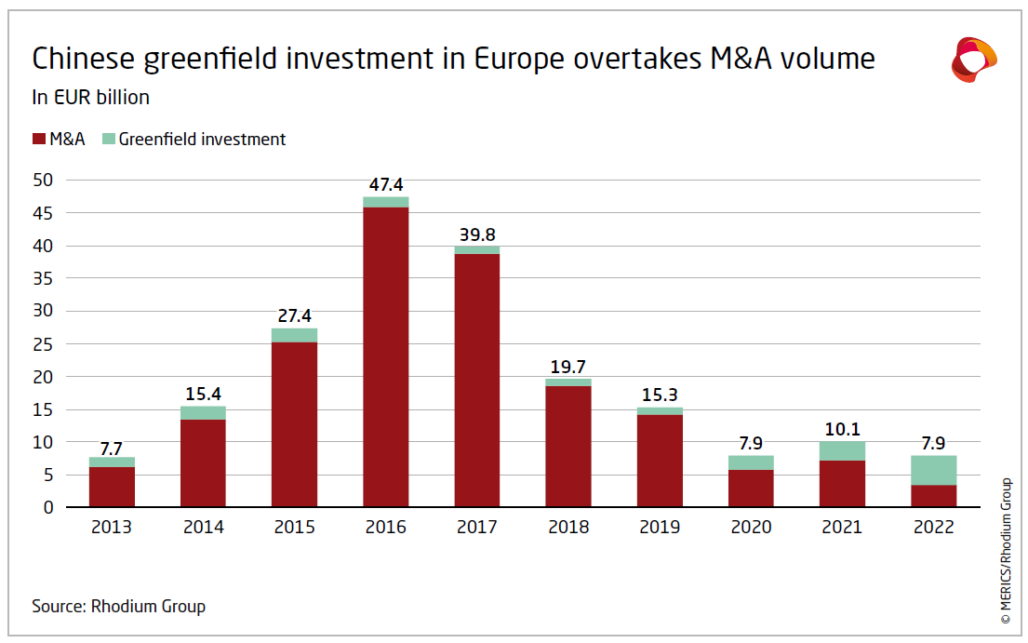

Another interesting feature is that greenfield investment overtook M&A for the first time since 2008 (see chart). Driven by electric vehicle (EV) and electric battery plants (gigafactories), Chinese greenfield investment in Europe increased by 53%, accounting for €4.5bn in 2022 or 57% of the total, exceeding M&A flows for the first time since 2008.

As regards European countries where Chinese OFDI took place in 2022, it remains concentrated on the “Big Three” and Hungary: 88% of Chinese OFDI flowed to just four countries, the [traditional recipients] “Big Three” European economies (the UK, France, and Germany) plus Hungary. All four received major greenfield investments by Chinese battery makers, as well as most of the year’s M&A activity.

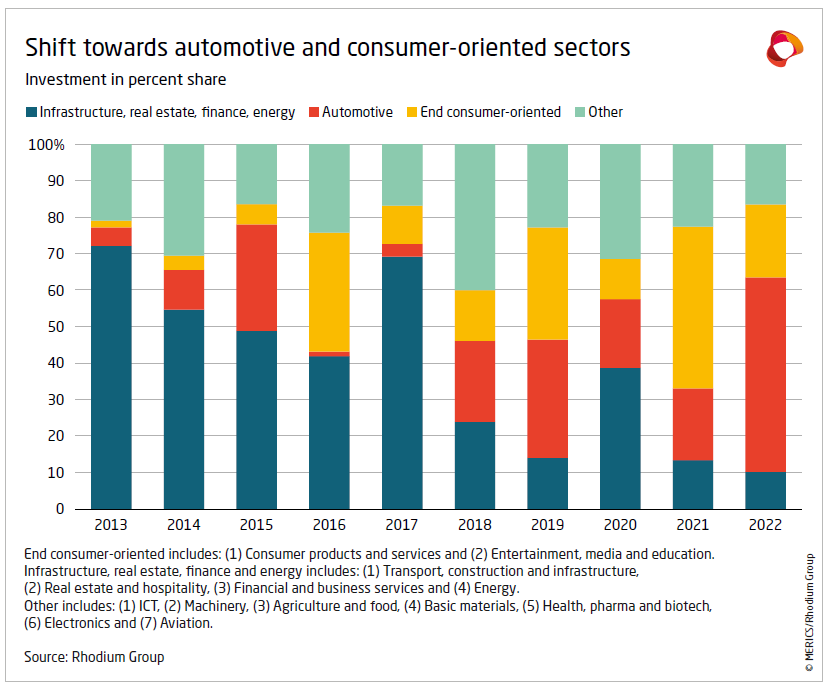

The main sectors (3/4 of the total) where Chinese OFDI in Europe has flowed were “consumer products” and “automotive“, as in 2021.

Another feature of Chinese OFDI in Europe is the concentration of investment on a very small number of large corporations. Albeit this pattern was somewhat already there before, in 2022 the level of concentration has intensified: 72% of total Chinese OFDI in Europe stemmed from just five investors, including CATL and Tencent. Both the type of investor and the nature of investment have changed as well. A decade ago, investors were primarily major SOEs acquiring European firms. In 2022, Chinese corporations are mainly private firms investing in greenfield projects in Europe.

For Q1 2023, Ernst & Young data shows China overseas M&As in Europe totaled US$952 million, down 39% y-o-y; there were 32 announced deals, down 24% y-o-y. Investment in the UK (on the real estate, hospitality & construction sectors) and Germany (on advanced manufacturing & mobility sectors) collectively took up 86% of the total value.

What are the reasons?

What are the reasons for this [continued and gradual trend of] falling Chinese OFDI in 2022 (apparently continuing into 2023)?

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), global direct investment flows dipped after the first quarter of 2022 due to the global crises triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The war escalated inflation as food and energy costs soared, leading central banks to hike interest rates in advanced economies. The resulting economic uncertainty and shifts in global financial conditions have spread caution and suppressed investment. Chinese companies involved in OFDI seem to have followed this general path of caution.

On a domestic level, China’s zero-Covid policies (only lifted at the end of 2022) and the economic disruption it provoked probably also took a toll.

Other endogenous factors that contributed to the said fall of Chinese OFDI (in Europe and elsewhere) last year were: (i) the ongoing domestic constraints on outbound capital flows; (ii) the policy of financial deleveraging; and (iii) economic uncertainty caused by China’s crackdown on its biggest tech companies with new regulations on fintech.

The historical background

However, to analyse other factors that probably created strong headwinds for relevant Chinese companies involved in OFDI decisions in 2022, it is important to look at the historical background in the preceding years.

First, one should take into account the restrictions imposed by the US authorities on almost 600 relevant Chinese companies – deemed to be “Communist Chinese Military Companies” (CCMC) – that led to the delisting from US securities markets of several of them (through the US President’s Executive Order 13959, superseded by Executive Order 14032, it is now prohibited for any US entity to own or transact (except to divest) publicly traded securities, or financial products derived therefrom, of companies that the DoD has listed as CCMC), the creation of blacklists (compiled under the “Entity List”), and led to the US Treasury forbidding any “US Person” to interact with them. This aggressive posture of the American authorities is part of a decoupling strategy that intends to exclude relevant Chinese companies from US markets and/or US technology. Simultaneously, the “trade / tariff war” with China initiated by the Trump Administration and continued by Biden’s Administration led to several disputes at the WTO.

This should have led Chinese companies on the path of internationalisation to focus more on Europe. There are compelling reasons for Chinese companies to invest in Europe: demand for European innovation and technology, the need for integration with European value chains, compliance with European regulations and avoiding regulatory hurdles, clear public policies on climate transition, and internationalisation to markets with high disposable income.

Furthermore, at the end of 2020, China and the EU concluded [an “agreement in principle” on] a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI). The aim of CAI was to create a more open, transparent and secure environment for greater future flows of investment, within an open multilateral trading system framework supported by both parties. However, in May 2021, the European Parliament passed a resolution to freeze ratification of the CAI in response to Chinese sanctions on European human rights advocates following EU-imposed sanctions on Chinese officials involved in alleged human rights violations in the region of Xinjiang.

In 2022, EU-China relations deteriorated further in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine war, as China and European countries found themselves on opposite sides of the conflict. In addition, European countries have also been under pressure from the US to distance themselves from China as the US seeks to decouple its economy from China.

European public opinion on China

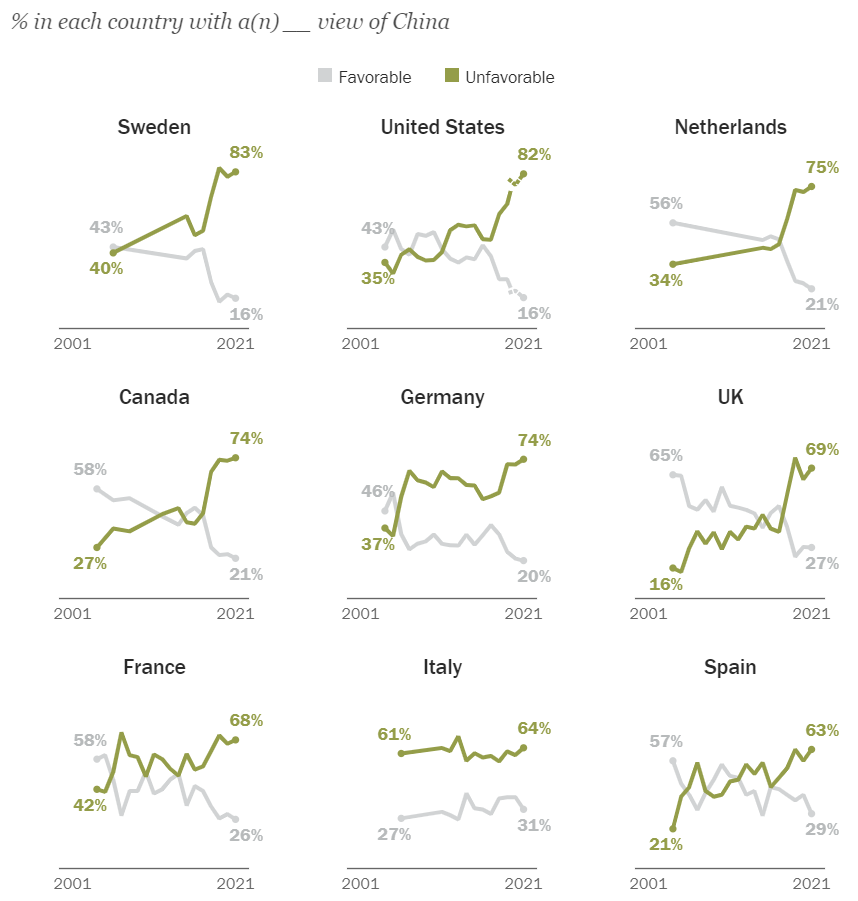

Also, during the last few years, several polls show that Western and European public opinion on China [and the Chinese government] has become more and more unfavourable, in some cases strongly negative. The charts on public opinion on this subject in several western countries published here – extracted from the Pew Research Centre poll published in September 2022 – is a good example. Depending on the country, the trend is clearly towards unfavourable views, accentuated in the last decade. In southern European countries, the trend is also there but not as strong.

This shift in European public opinion was realised by many Chinese companies and made them wary of a European venture. The risk assessment by banks and financiers also became more prudent when considering the internationalisation of Chinese companies in Europe.

European restrictive rules on Chinese investment

In line with this new unfavourable trend in European public opinion, and fearful of a rising “systemic rival” that still has not opened its market in equal terms to European companies, the European Commission and several European countries introduced restrictive rules tightening OFDI in the EU, mainly aimed at Chinese companies, in particular SOE.

According to the abovementioned MERICS-Rodhium report, one of the key reasons for the low Chinese OFDI was an increased scrutiny by European governments of Chinese investment, as European governments seek to decrease their economic reliance on China. The said increased scrutiny, via tightening investment screening measures, impacted Chinese acquisitions of strategic assets such as European semiconductor companies and critical infrastructure. MERICS-Rodhium researchers found that at least 10 out of 16 investment deals pursued in 2022 by Chinese entities could not be completed in the technology and infrastructure sectors, principally because of objections raised by authorities in the UK, Germany, Italy, and Denmark.

According to the abovementioned MERICS-Rodhium report, several of the aborted deals, such as proposed semiconductor acquisitions in Germany (Sai MicroElectronics’ proposed acquisition of the automotive chip assets of Elmos Semiconductor) and in the UK (Hong Kong’s Super Orange buying electronic design company Pulsic), were blocked following reviews into the specific technology targeted by the Chinese investor. In other cases, deals already agreed upon were annulled (Italy’s annulment of the sale of a military drones’ group, Alpi Aviation, to Chinese state-backed companies) or collapsed after the imposition of regulatory stipulations, the report added.

These review mechanisms on relevant M&A in strategic sectors, sensitive technologies, and energies are likely to be expanded in 2023 and are coming into effect in Belgium, Estonia, Ireland, and the Netherlands.

In any case, while screening of Chinese investments in Europe has increased, the region still remains more politically open to China than the United States, which has cracked down on Chinese battery imports and imposed other restrictions on Chinese companies via the Inflation Reduction Act.

Main fields where Chinese companies are investing in Europe

The main fields where Chinese companies are increasing investment in Europe are: (i) the automotive sector; and (ii) the consumer-oriented / retail sector.

Chinese OFDI in Europe is now directed to sectors where Chinese private conglomerates are highly competitive, like automotive, more precisely the electric vehicle (EV) value chain – both on electric battery plants (also known as gigafactories) and on EV plants – or end consumer-oriented sectors like video gaming or household products.

The leading sector for Chinese OFDI in Europe, in 2022 and most likely for the coming years, is the automotive one. As Europe becomes the world’s second biggest EV market after China, the Chinese companies producing electric batteries and EV want to use their expertise to enter this key strategic sector and grab a sizeable portion of the European market. Europe has a good charging infrastructure and generous government purchasing subsidies, developed within a clear public policy on energy transition aiming at decarbonizing road transportation.

Furthermore, unlike other major automotive hubs (such as Japan or South Korea) Europe

has few gigafactories or battery firms of its own and is therefore still open to Chinese investment in this field. Whilst the commitment in the sector of electric battery plants is clear and includes almost all the big Chinese groups in the sector, the same cannot be said as regards the main Chinese EV manufacturers. Economic history teaches us that the current easy EU-certification of Chinese-manufactured EV will not last long, hence the sagacity of producing a sizeable portion of EV for the European market within Europe before a new “Fortress Europe” policy is raised. However, many relevant Chinese EV manufacturers have not realised it yet. They will probably realise it in the short term.

The trend of Chinese investment in Europe is clearly downwards, having fallen to its lowest point in almost a decade last year. Uncertainty fueled by unfolding geopolitical tensions, the war in Ukraine, changes in European public opinion on China, and greater scrutiny by European governments and agencies, is not likely to lead to a new era of vast amounts of Chinese capital flowing into Europe.

The main driving sector for Chinese OFDI in Europe will probably remain the automotive one. It is possible that overall considerations on friendly countries to Chinese investment will influence investment decisions by relevant Chinese investors, in particular as regards greenfield investments. The “Big Three” European economies will likely continue to be the main destination of Chinese investments, but southern European countries may well be another preferred destination for these greenfield investments.